“Pressure cooker” impact of touring on mental health “needs addressing” – but help is at hand

Read the original published article at NME.com

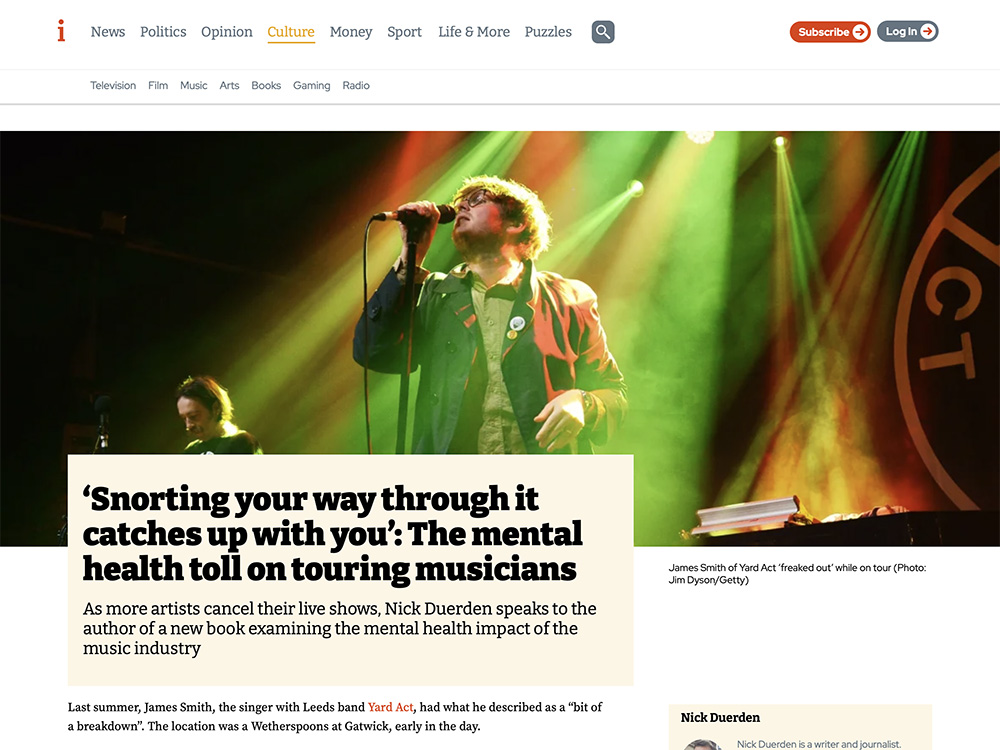

Figures from the music industry have spoken to NME about the “dangerous” impact that touring can have on musicians, while offering up help and advice for World Mental Health Day.

As mental health charity Mind have reported, research has shown that people working in the music industry are “more prone to mental health problems than the general population”, with “musicians being up to three times more likely to suffer from depression”. Financial pressures, isolation, lifestyle, hectic schedules and addiction are often named as factors.

Recent years have seen the likes of Lewis Capaldi, Sam Fender, Shawn Mendes and Wet Leg all cancel shows while citing mental health as the reason. Another to take themselves off the road was Editors guitarist Justin Lockey, who sat out of the band’s summer 2022 dates due to “struggles with anxiety”. Speaking to NME, Lockey detailed what led to his decision – and what he’s done since to improve his lifestyle.

“It was post-COVID, and the first show back after a year and a half,” said Lockey. “I remember being quite worked up for it and anxious anyway, then I got on the flight to a warm-up show in Porto and collapsed.

“We’d just spent nearly two years of everyone just hanging out at home and working remotely, then suddenly getting back to what I was always nervous about doing anyway – which was touring and travelling – and it all just came to a head. I got taken off the flight, taken to hospital and decided that I wasn’t ready to go back to that full-on life.”

Lockey, also a member of Yourcodenameis:milo and formerly Mastersystem with the late Scott Hutchison of Frightened Rabbit, explained how his decision to take a break from touring was “about knowing that you have limits”.

“It is a completely different life, and a lot of people who aren’t in bands or in the music industry think that touring is this non-stop party of just waking up in different cities, after-shows and great gigs – but it’s not,” he said. “It can be a very isolating, lonely and strange existence. You’re not in the same routine as most of the rest of the planet.

“No one outside of music understands your routine. You tell them you’re in Rome and they think you’ve got such a cool life, but they don’t see the 14 hour bus journey to Rome or what the constant travel does to you. It’s like cabin fever times a thousand.”

Lockey described touring as “an ordered chaos of a life” with “a lot of the time just sat around waiting to do something” among the pressures of performing.

“It’s so cliché but you can see why so many bands throughout the ages have turned to drink and drugs – because there’s nothing to do and that’s really available,” he said. “For anxiety and mental health, it’s an absolute crusher. Especially if you’re on a long haul tour, like a five weeker around Europe – imagine it’s winter, dark, freezing cold, you’re halfway through your tour, you’re playing pretty much the same set every night.

“The only thing that might change is the language and the currency, but everything else is the same. Soundcheck is at the same time, dinner is at the same time, shows are at the same time, it all becomes like a black hole.”

He continued: “A lot of bands – especially young bands – they hang out together, they live together, then they’re in the studio, then they’re on tour, and there’s no separation so you get sucked into this weird bubble. It’s not a real life. Time moves at a different rate to everyone else. You come home and it feels like everyone else’s lives had moved on but you didn’t realise because you were away in this mad bubble.”

The musician described how his anxiety can “flare up” and lead to issues with eating and sleeping. As well as his hiatus from the road, Lockey said that he’d been managing touring life much better now that he had find “elements of life away from music” – leading to the creation of his new sci-fi podcast drama The Salvation, starring Ariyon Bakare, Rose Leslie and Toby Jones

“A few years ago, I started spending all my spare time on script-writing and photography, so that when I was trapped in hotels day in, day out, I just wrote scripts,” he said. “Now I’ve got a series on the go, and that’s the rest of me trying to fill the gaps in my brain where anxiety would have taken me. Make use of your life and time outside of the band. When you come into the band, you’re in it.”

He continued: “Eventually I realised that you had to find something that wasn’t the band to dip into. You need an obsession that’s not a career. Find a hobby that can be just as much of a creative outlet and obsession as music is, but it isn’t music. There’s no manager, record label or agent there, and you don’t have to do press about it. You’re just going out to do something for yourself: walking, swimming, drawing, painting.

“In music and when you’re in a band, you do feel like your identity belongs to this big travelling circus. You struggle to find your own identity because you spend so much time being lumped together with other people. We’re all very close and we love each other, but there has to be your individual self.”

That extended to Lockey deciding to “take himself out of the touring party” and travel alone between shows, “turning the anxiety into excitement” of what the journey will bring. Another thing adding to the “pressure cooker of a very strange life” however, was the influence of social media.

“You can keep scrolling and there will always be something new to see,” he said. “You can’t complete it, and it just stops you from doing things. Being in a band, they might tell you that you need to be on 17 different forms of social network for people to know you exist – but take a break.

“Being sucked into that world can really harm you – especially if you’re young and coming into it. Now you have to work twice as hard to get out of it what you would have done 10 years ago, so you’re twice as likely to slip into this feeling of exhaustion and not knowing who you are or where you belong. Nobody starts a band to be on social media – you start a band because you love that feeling of feeling the reaction to your music in a room.”

While also admitting that there was a comedown and adrenaline crash after coming off tour, the artist said that a musician’s life “is governed in campaigns rather than time, but there are ways you can plan for it”. Lockey said that he was comfortable that his life is now “completely changed” having “totally changed the balance and put my interests up to a point where I can be cognitively focussed when I’m not doing music, but the other disciplines make you more excited about music”.

“Even my bandmates have commented on how much better I am at touring,” he said. “I’m just a lot more comfortable and doing what we do. It has taken me a decade to get to that point.”

While hailing the number of services that are now at hand to musicians struggling with mental health and how it’s now “a lot easier to talk this about than it was a decade or two ago”, the musician and writer said he felt that there was “still a stigma”.

“This could end people, and the bottling up on emotion is too old-school,” he said. “The ancient English cliches of ‘get over it’, ‘move on’ or ‘man up’ are so dangerous. They make people afraid to ask for help. We need to reassess how we do things. The sliding slope of mental illness is very steep. You can get to a very dark place very quickly.

Lockey added: “I’ve lost a few friends who have taken their own lives over the years, and things could have been so much different. Conversations could have been had, and that bothers me. As much as music is brilliant and life-affirming, it’s not worth more than your health and never will be. What have you got at the end of it?”

Tamsin Embleton is a psychotherapist and former tour booker, as well as the author of the acclaimed book, Touring and Mental Health: The Music Industry Manual – a 600-page book that provides “touring guide for musicians will help artists, tour managers, production managers, crew, and artist teams to identify and cope with the various psychological difficulties that can occur during or as a result of touring”.

Written alongside psychotherapists, performance and vocal coaches, dieticians, psychologists, and sleep, sexual health, and addiction experts, the book features interviews with the likes of Nile Rogers, Four Tet, Radiohead’s Philip Selwayand more while providing “practical guidance, resources, psycho-education” and more for those in the industry looking for the best ways to handle life on the road without suffering burnout, anxiety or depression.

“This is an industry that attracts quite complex, interesting, quirky people; many of whom are grappling with stuff behind the scenes,” Embleton told NME. “I sent so many artists out on the road and I was working in venues, day in, day out. To be on tour is really intense, it’s a bit of a pressure cooker. Underneath the surface, what you’re already struggling with is going to intensify. You’ve got no personal space, and it hits you biologically, psychologically and socially.”

Admitting that by a large “artists aren’t prepared” for the realities of touring, Embleton said: “They’re sold a bit of a dream about how it’ll be, and all the exciting stuff is true and real, but those highs are quite a lot for your body to process and come down from. You don’t get great sleep, you’re eating party food most nights, then there’s the abundance of substances, and the mentality that every gig needs to be a party.”

Describing the nature of “every show being marked with booze”, Embleton explained how alcohol and substances were “embedded in the culture” of live music; something that will always “have an impact on your anxiety the next day”.

“We talk about how venues can provide dry dressing rooms and better alternatives for people that don’t drink, or don’t want to drink,” she advised. “It has all of these secondary impacts, and a lot of addiction forms on the road. As long as you can do your job, as long as you’re high functioning in one area, then the rest of it is often overlooked. It’s a coping mechanism, but it’s not the only one.

“Artists tend to be more reflective and responsive to things in their environment. We need them to be like that in order to create, but it also may leave them more vulnerable in certain high stress scenarios.”

The writer agreed with Lockey that touring could be made much easier without an onus on social media as well as “placing importance on relationships outside of music”.

“Music can be bit of a one-stop-shop,” Embleton explained. “It’s obviously a workplace and, and relationships are usually informal. You build a lot of friendships, but that can you very vulnerable if you leave the industry or just step away. Often that’s quite a shock.”

She continued: “Then of course, there’s the very modern social media aspects of being an artist – constantly being either under the microscope or feeling like they need to engage. That’s probably quite a new concept to the music industry. There’s always been press, but there’s not been this level of needing to share your every day.”

Citing a chapter in her book by Peter Robinson from Pop Justice – also a therapist and a coach on dealing with the media – Embleton advised artists to have “boundaries in place in order to feel separate from the online self and the real self”.

“What can you do with the time off?,” she began. “Don’t tell people about it via social media, otherwise this is going to become content. It’s a very distorting thing when your life becomes content. It has become measured with the metrics that we measure all things with these days – streams, shares, likes, numbers and engagement.”

Embleton added that while the crisis “needed addressing”, music was ultimately “a stressful industry”, one that’s “turbulent, unpredictable”, “exposes you to a lot of criticism”, and not often willing to change.

“It also challenges to your relationships because your job is front and centre,” she said. “You’re not taught how to navigate that. The industry tends to focus on saying, ‘Let’s make this individual more resilient so that they can cope’, rather than say, ‘OK, well, maybe we can change some work practices’. The truth is we need a bit of both.”

While touring remains “unregulated” in terms of the intensity of schedules and what’s expected of artists, Embleton said that she wanted her book to help those managing tours be able to better steer the ship to avoid catastrophe.

“Touring is a rollercoaster and we’ve got to help people navigate the highs and the lows and kind of understand the stress response in the body,” she said. “We talk a lot about pacing, capacity and duty of care. I interviewed about 80 people for the book, including a lot of tour managers. Looking back a lot of them thought, ‘I facilitated some addictions’ – including sex and porn addiction, which is quite big on the road – or they’ve not dealt with stress well.”

She went on: “I was talking to like Jim Digby, who used to look after Linkin Park, about how they navigated the fall-out of Chester Bennington’s suicide. They set up a group therapy session: it turned out somebody else was feeling suicidal, so they were able to get them help. That shows how we can be helping people navigate the emotional world of touring and being in a band while being practical.”

Visit here for more information on Music And Touring: The Music Industry Manual.

While also pointing out the number of services that are now available to struggling musicians alongside her own therapy group ran alongside music industry professionals, Embleton said that she hoped the growing community voice would help spread awareness of better coping mechanisms, as well as advocating for better mental health in live music.

“We’ve got really high rates of, addiction, suicide, anxiety and depression, in artists, crew, and touring people,” she said. “I’ve had so many people around the world say to me, ‘We’ve needed this – I wish I had this 20 years ago’. Hopefully we’re going to help a lot people recognise early warning signs and get people help and slow down a little bit.”